Throughout adulthood, I’ve rarely discussed the afterlife with others beyond poetic musings of what animals might be doing in heaven.

Seriously.

One of my incessant questions as a child was, “Are there dinosaurs in heaven?” And if you know anything about conservative American Protestantism, clearly my five-year-old questions were already knocking at two shibboleths.

Even so, I don’t remember my question being weird or shush-shushed by well-meaning adults, so my imagination had a mind of its own. If anything I gravitated toward a form of “universalism,” but I didn’t know that word and didn’t have a theological language for my beliefs. I’d call it something like “Just a Good Universe.” (I promise I won’t start a denomination over it.)

everyone’s talking about hell

Little did I know that for the last 15 years, conversations about hell and universalism (aka universal reconciliation) had gone wildly mainstream. Was it The Shack? Or Rob Bell’s book? Or the “outing” of some very public theologians who didn’t believe the traditional eternal torment of hell (a situation Bradley Jersak humorously describes in this book)?n

It’s probably a combination of all of the above. I wouldn’t know, because around the time The Shack began making its rounds I’d stopped paying attention to a lot of mainstream Christian media. Even the “emergent conversation,” in which I was tangentially involved, didn’t hold my attention. So I missed the Rob Bell train.

Over the last two years, I began to get interested in making sense of what seemed like the evangelical church’s need to constantly defend itself, and I thought it was time to crack open some actual theology books.

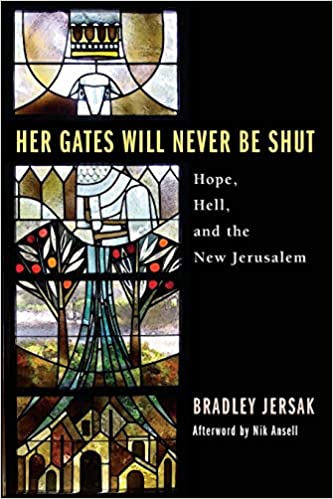

That’s what brought me to the book, Her Gates Will Never Be Shut. Several friends recommended it to me as a gateway into the doctrinal history of universalism. I’d also like to understand the conversation because it matters. As Jersak writes, what we think about hell affects our activities, pastoral concerns, and view of suffering, and most of all, how we view God.

So enough introduction.

Title: Her Gates Will Never Be Shut: Hell, Hope, and the New Jerusalem

Author: Bradley Jersak

Pages: 234

Publisher: Wipf & Stock Publishers (November 30, 2005)

start here

I’d recommend this book as a starting point on the topic of universalism (or the version Jersak calls “hopeful inclusivism”) within Christian thought. While it explores the topic of ultimate destiny and universalism, it is focused on the various Biblical and historical concepts of judgment itself.

The first half is a marvelous combing out of the history of beliefs on hell and judgment. Jersak gently untangles various and often frequently conflated “locations”—the abyss, Scheol/Hades, Gehenna, the lake of fire, and Tartarus.

Along the way, he shows how the diaspora and oral tradition shaped the Jewish imagination around these concepts. Most Christians are unaware of early church history or Christian traditions outside their own. This book goes a long way to explaining how concepts grow, synthesize, and take hold through literature, current events, and theological shifts.

The rest of the book includes an exposition on Revelation (and other apocalyptic discourse), including a beautiful chapter on one of Jesus’ parables of judgment. He writes this chapter as a meditation in a Lectio Divina-style conversation.

a pastoral tone

This brings me to one of the strongest aspects of this book: its sensitive tone and pastoral asides. I appreciated Jersak’s careful approach and his frequent pauses at certain points to say, “This is where I land,” or “This is my personal bias.” And he intersperses his footnotes with emails from a theological sparring partner who has differing views. That demonstrates intellectual humility.

Most scholars get so rigid about their theses, often forgetting that sheep that need shepherding. And he knows he is tackling a subject that has frightened children. Jersak allows for different interpretations and admits his lack of conclusion on some things. Then he highlights how the early fathers didn’t have unequivocal agreement on the topic of ultimate judgement.

This book’s biggest strength is that it is bent on context.

It’s not convincing its readers what to believe, but why we might have come to believe the things we do. And most Christians just don’t know where some of our ideas come from. (Even when we think they are straight “from the Bible,” it is often a particular interpretation of it.)

For example, one of the most helpful parts of the book for me was in his explanation of the origins and development of purgatory. I learned that it had some fleshings-out in the early church fathers but Augustine developed it into a far more rigid and punitive doctrine, which the Catholic church has since repudiated. This chapter alone–and its insight into doctrinal reforms within modern Catholicism–was worth the entire book. In some areas, the Catholic church has gone much further in reforming its views on judgment and hell than many evangelicals!

last thoughts

I didn’t pick up this book looking for answers about hell or the afterlife. If anything, my questions are more about the here and now—I want to experience and share the life promised here.

But now I have some context, and a language, to flesh out the hope that I have always imagined. It has helped me understand the larger conversation. It clarified differences between Christian universalism, a broad “all gods lead to heaven” universalism, universal reconciliation (called apokatastasis in the early fathers), and other possibilities. This topic creates all sorts of conflicting ideas in the church about justice, reconciliation, perfection, and even the resurrection. Jersak touches on all of these ideas.

If anything, this book has gotten me curious about the early fathers, and that’s a good thing. As C.S. Lewis wrote in his introduction to Athanasius’ On the Incarnation, it is a good rule to read an old book after every new book because it “puts the controversies of the moment in their proper perspective.”

Credit: Photo by Bram Bakkers. (Read about photo use here.)

*Disclosure: This post contains affiliate links. If you click through and make a purchase, I’ll earn a commission, at no additional cost to you. This helps support my work. Read my full disclosure here.