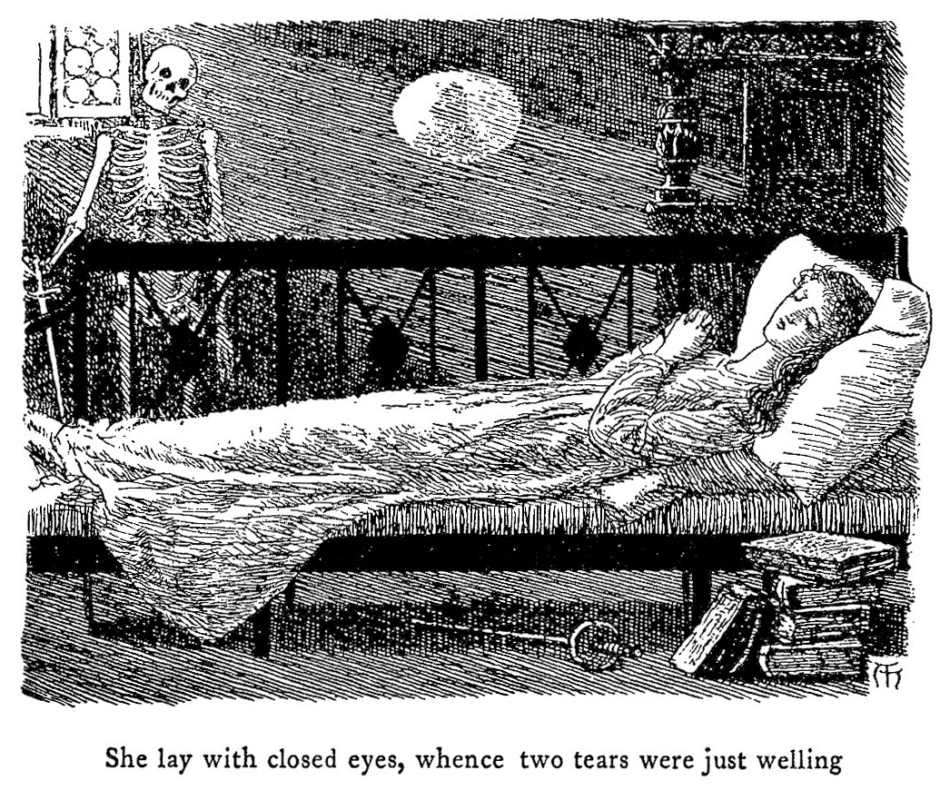

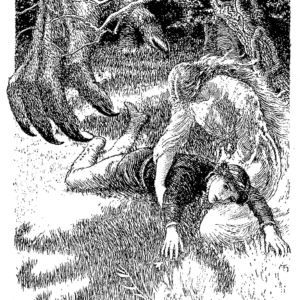

I constantly imagined, however, that forms were visible in all directions except that to which my gaze was turned, and that they only became invisible, or resolved themselves into other woodland shapes, the moment my looks were directed toward them.

Phantastes by George MacDonald

Fifty pages in to Phantastes, I recognized that George MacDonald was at it again.

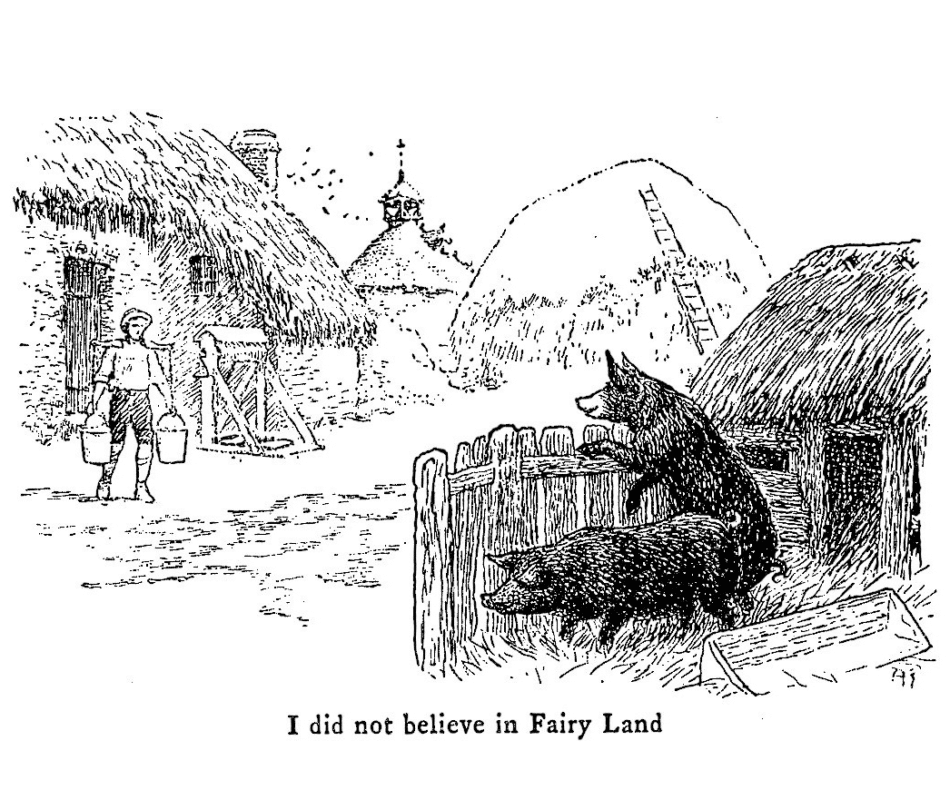

Couched in a story that was ostensibly going to be about fairy realms was a far more obtuse story about an unnamed narrator’s “fairy sight.” Like many of MacDonald’s stories and novels, the plot and characters fade into the background–and in the foreground is the true main character, the imagination itself.

I know I’m not the only one who has been dazzled by MacDonald’s often disjointed narratives and abrupt endings. C. S. Lewis famously wrote in the introduction to his MacDonald anthology: “Few of his novels are good and none are very good.”

But as most fans of MacDonald may tell you, there is something else going on in his stories that makes them worth reading.

a priest of the imagination

One might call MacDonald a spiritual allegorist, but this makes it sound like he was only interested in writing stories that were sermons in disguise. And that’s a fair charge, since in many cultures fairy tales were often written in the service of teaching children morals or virtues. But MacDonald did something entirely unique with this genre. His tales go way beyond the bounds of allegorizing.

In the introduction to Phantases, Lewis wrote, “What [Phantastes] actually did to me was to convert, even to baptise… my imagination.”

I’ve thought quite a bit about what he meant by that.

When we read a story, or watch a movie, we are able to be carried along by the author’s imagination and all the details they provide. In fact, we want to know who the author is imagining. Most of the time we aren’t aware of where and when we are filling in the blanks that haven’t been provided. At some level we trust where the author is going.

MacDonald seemed so keenly aware of how we fill in those blanks. He understood that so much of how we experience art involves a very personal inner revelation. And his stories make room for the imagination to play. Sometimes I feel as if I am making stuff up out of thin air as I read them.

A fairytale, a sonata, a gathering storm, a limitless night, seizes you and sweeps you away: do you begin at once to wrestle with it and ask whence its power over you, whither it is carrying you? The law of each is in the mind of its composer; that law makes one man feel this way, another man feel that way. To one the sonata is a world of odour and beauty, to another of soothing only and sweetness. To one, the cloudy rendezvous is a wild dance, with a terror at its heart; to another, a majestic march of heavenly hosts, with Truth in their centre pointing their course, but as yet restraining her voice. The greatest forces lie in the region of the uncomprehended.

from “The Fantastic Imagination”

Because his stories seem to pay more attention to the “meta-subject” of that imagination than to the characters and storytelling flow, they often can float around in disjointed ways. This is very true of Phantastes, one of his early novels. The main character goes through a series of events that are about encountering a spiritual realm he cannot describe except in shadowy language.

the theologian

Fifteen years ago, the only people I knew who read MacDonald were usually avid readers of fantasy, many who had discovered him through the work of C. S. Lewis. But he has since grown in popularity, particularly because of his gracious view of God that was askew from the Calvinism of his time.

Much of the current interest in MacDonald foregrounds his theology, particularly his views on universal reconciliation. (It is, after all, MacDonald’s influence that looms over Lewis’ The Great Divorce, which is the best book on “hell” I’ve ever read.) And while this is understandable, people miss something when they use or read MacDonald only in the service of theological ideas.

MacDonald’s sermons aren’t the same type of apologetics we expect from a writer like C.S. Lewis. MacDonald’s “theology” is hidden inside of a different sort of epistemology. His writing is steeped in the fragrance of relationship. He teaches me how to think, not what to think. It wafts over me as I read, even in his sermons, and draws out my curiosity, especially about the Father, in childlike fashion.

in George MacDonald there is both a gem of a mind and heart we rarely hear in any other Christian writer. Especially within modern evangelicalism, “mystic” and “theologian” tend to be separate categories of profession or even thought, but the two meet in MacDonald much like they meet in some of the early church fathers. My term for what MacDonald writes in his sermons is “revealed theology”—I read him for devotion and contemplation as much as for ideas.

“but I don’t get it”

If you are new to George MacDonald, and swim in theological circles, you will often hear people speaking glowingly of his Unspoken Sermons. I couldn’t agree more—if I had to pick one desert island book, that’d be it.

However, on first encountering MacDonald, many discover that his language is dense. The sentences are long. His paragraphs can stretch for pages. (I sometimes mentally insert my own periods!) There are turns of language that would have been more easily understood in late Victorian England than they are now.

But most of us have no trouble reading Pride and Prejudice, Jane Eyre or Dracula, which were written decades before MacDonald was writing.

I think the problem that readers have is less with his literary style and language and more with his way of thinking.

I like to call MacDonald a spiral thinker. He will start with one topic and sometimes end up at another. Or he’ll spiral around a main theme and run poetic and tangential circles around that central theme. Even his most beloved novels such as Phantastes and Lilith never move in a straight narrative direction. His thoughts often wander around timelines into fascinating sub-stories, which can be difficult if you are expecting linear storytelling.

If you are a slow reader, or unaccustomed to Victorian language, I’d recommend you start with either C. S. Lewis’ wonderful anthology or Phantastes. This is a shorter novel that will give you a sense of his rhythm and mind, a wonderful introduction to the way MacDonald “talks.”

His fairy tales are even better. Many of them are quite humorous and fun to read at night! You’d also be surprised how easily children follow the strange universes of these stories. Once you get used to his tales, digging into his sermons will feel a little easier.

Above all, relax and don’t worry if you don’t understand every tangent. Give your imagination a chance to play. 🦄🧚♀️

Recommended

- The Complete Fairy Tales

- Phantastes

- George MacDonald: An Anthology, edited by C.S. Lewis

- Unspoken Sermons (Vol I-III)

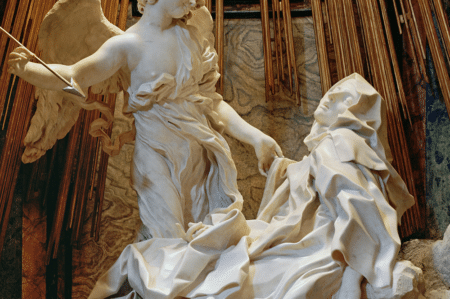

Credit: Illustrations by Arthur Hughes from the 1905 publication of Phantastes, via St. Norbert College

*Disclosure: This post contains affiliate links. If you click through and make a purchase, I’ll earn a commission, at no additional cost to you. This helps support my work. Read my full disclosure here.