Here we are smack dab in the middle of Lent.

And along with it a flurry of mixed messages about what it means to repent. Repentance is a hard subject to talk about without offending one tradition or another, but I don’t mind saying that repentance is an overused word.

We have hijacked its meaning for far too long!

Just looking at the somber and/or chastising tone of certain messages, I gather that many wilderness-parked prophets and priests think repentance is more about self-effacement and sobriety than it is about the joy of simply changing your mind.

Yes, there should be joy in it. As one of my favorite theologians likes to say, “Be ye transformed by the blowing of your mind!”

Repentance vs. Metanoia

The term “repentance” came into use with Jerome’s Vulgate Bible in the 4th century. Rather than transliterate the unique Greek word μετανοεῖτε (metanoeite), Jerome chose the phrase Poenitentiam agite—meaning to “do penance.” Other translators thought it was a poor translation, but poenitentiam persisted in the Latin and then later in English as “repentance.”

Just a few examples of those issues:

- Tertullian protested the use of Poenitentiam agite and suggested conversio, which is close to “turning around.”

- In the early 1400s a priest named Lorenzo Valla began studying Jerome’s Vulgate, and pointed out many errors Jerome had made. This included the poor translation of metanoia. He also questioned the church’s use of penance and indulgences, but the Vulgate-loving majority forced him to renounce the changes.

- Erasmus translated metanoia into the Latin as resipiscite, which is closer to the concept of “changing your mind.”

These men knew the concept of penance was foreign to the New Testament, along with “re-penance” (repeated penance). But somehow, that hasn’t stopped the majority of the Western church from embracing “repeated penance” in other subtle forms. We often think of repentance to public or private confession of one’s sins. And then we tie that to forgiveness (from God or others). So there is often still a codependent price tag attached to forgiveness. We might not be demanding medieval cash, but we’re still demanding some kind of “work” to earn our absolution.

Martin Luther had a lot to say about this:

Then I progressed further and saw that metanoia could be understood as a composite not only of “afterward” and “mind,” but also of the [prefix] “trans” and “mind” (although this may of course be a forced interpretation), so that metanoia could mean the transformation of one’s mind and disposition. [Accepting damage and recognizing error] is impossible without a change in one’s disposition and love.

Continuing this line of reasoning, I became so bold as to believe that they [the translators] were wrong who attributed so much to penitential works that they left us hardly anything of poenitentia, except some trivial satisfactions on the one hand and a most laborious confession on the other. It is evident that they were misled by the Latin term, because the expression poenitentiam agere suggests more an action than a change in disposition; and in no way does this do justice to the Greek metanoein.

…While this thought was still agitating me, behold, suddenly around us the new war trumpets of indulgences and the bugles of pardon started to sound, even to blast, but they failed to evoke in us any prompt zeal for the battle. In short, while the doctrine of the true poenitentia was neglected, they even dared to magnify… only the remission of its least important part. Finally they taught impious, false, and heretical things with so much authority—temerity, I wanted to say—that if anyone muttered anything in protest he was immediately a heretic destined for the stake and guilty of eternal damnation.

Since I was not able to counteract the furor of these men, I determined modestly to take issue with them and to pronounce their teachings as open to doubt…

Martin Luther, Letter to to John Von Staupitz, MAY 30, 1518

The meaning of metanoia

In Classical Greek, metanoia had overtones of regret, but in most New Testament references it has little to do with self-deprecation, paying off a debt, paying for one’s sins, contrition, or public mourning. This is where Christians throughout history right up to the present time frequently conflate Hebrew practices of “teshuvah” (also translated into English as “repentance” and meaning “return”) and its overtones of atonement with the Greek concept of metanoia (“after thought”).

Luther understood that “repentance” as it occurred in Scripture had been overstuffed with legalism. Yet despite his great reforms that would curb abusive church practices like penance, indulgences and absolution, “penitence” lingo has lingered in most church traditions. And it affects our thinking about it.

So what is a good definition?

Luther’s is great: a change in disposition.

My favorite is simply this: change your mind!

I also love this Greek Orthodox definition of metanoia:

“The Greek term for repentance, metanoia, denotes a change of mind, a reorientation, a fundamental transformation of outlook, of man’s vision of the world and of himself, and a new way of loving others and God.”

The Greek Orthodox Diocese of America

This isn’t something we can force on ourselves. Nor is it something that happens by self-reflection and gazing into our own navels trying to find something wrong. It happens when we look at the One who reveals, in whom we see who we truly are. Christ’s revealing is often gentle and perfectly tailored to us. He doesn’t demand or threaten us into change; as we are told in Romans 2:4, “It is his kindness that leads to metanoia.”

Isaiah 55:8-11 also gives wonderful meaning to metanoia: “Your thoughts were distanced from God’s thoughts as the heavens are higher than the earth, but just like the rain and the snow would cancel that distance and saturate the soil to awaken its seed, so shall my word be that proceeds from my mouth.”

For me, metanoia is as simple as seeing the beauty of Christ. Whatever is good in Him is true of me–and that is what my Heavenly Dad thinks about me.

A Meditation

Oh how sweet you are, metanoia!

The image of Christ thrown back on me,

casting all beauty on limb, will and heart.

Leaving behind that pilgrimage of self

searching for self—circling a wasteland—

and arriving in You, the banquet of Yes.

I say yes to your yes, drink from your yes,

hear the toast to my life: it is good.

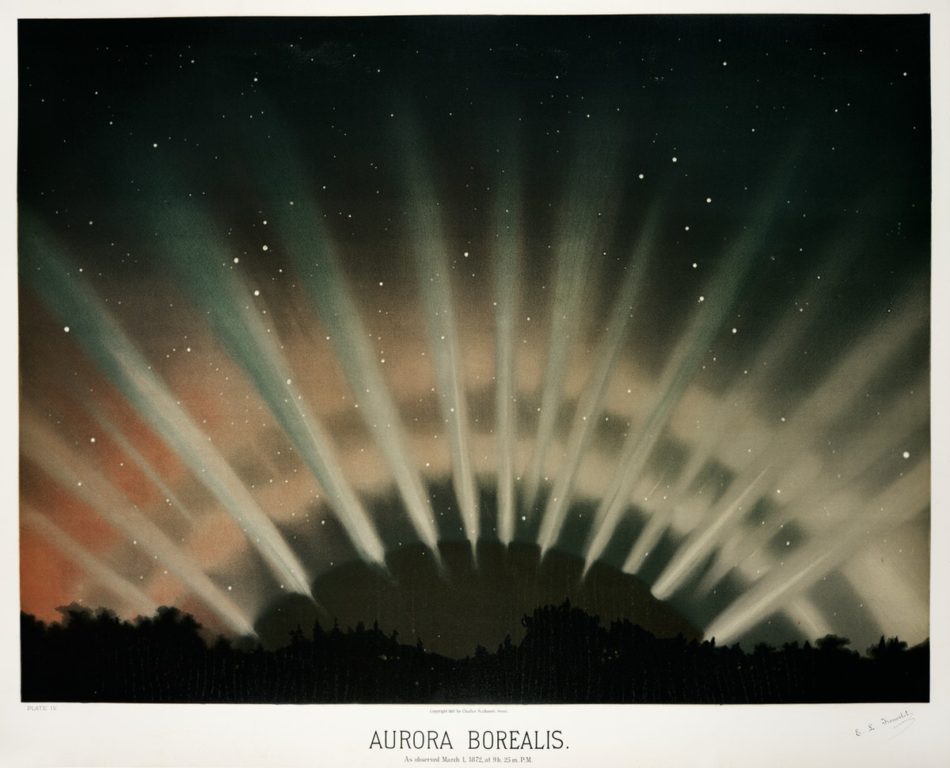

image: Aurora Borealis by E. L. Trouvelot, Raw Pixel. Read more about this.